Wear is typically defined as the gradual removal of material by contacting surfaces in motion. Though there isn’t a definite way to qualitatively measure the life of a component from wear alone, it is important to energy loss and linked to frictional processes.

Wear can be classified into several types. The more mechanistic ones are:

- Abrasive Wear

- Adhesive Wear

- Corrosive Wear

You can also have wear due to fatigue, melting transitions, chemical reactions among many others. The models most often used in DEM (discrete element methods not dust extinction moisture, new term I learned recently) use an abrasive wear or adhesive wear method. The Finnie Wear Model can be considered an abrasive wear type. A common adhesive wear type is the Archard Wear model.

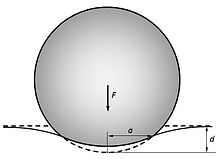

Used by some of the commercial DEM codes, or variations of it, the Archard wear model states that the volume of material removed is proportional to the work done by friction forces. It is a function of the sliding distance, normal load, hardness number of the softest contacting material, and a dimensionless wear factor or coefficient.

In its basic form, Archard wear is expressed in terms of wear depth. However, wear volume is the more popular approach. Since there are a number of versions to Archard wear and similar models done by Holms and Khrushchov it’s best to look through each paper. Here are some that may move you in the right direction:

- Archard, J. F. Contact and rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Applied Phys 24:981-988, 1953.

- Kauzlarich, J. J., Williams, J. A., Archard wear and component geometery. Proc Instn Mech Engrs. 215: 387-403, 2016.

- Rabinowicz, E. Friction and wear of materials. John Wiley, New York. 1965.

for a quick intro:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archard_equation